The Ides of March Then and Now

By Tappan Wilder

Being of a certain age and generation, I found myself assigned in high school to study Latin. It proved not a happy experience, and after a painful year I was glad to migrate to German. As a result I joined fellow refugees who choose to allow The Ides of March to pass with little comment to avoid being reminded of Latin and especially of Julius Caesar.

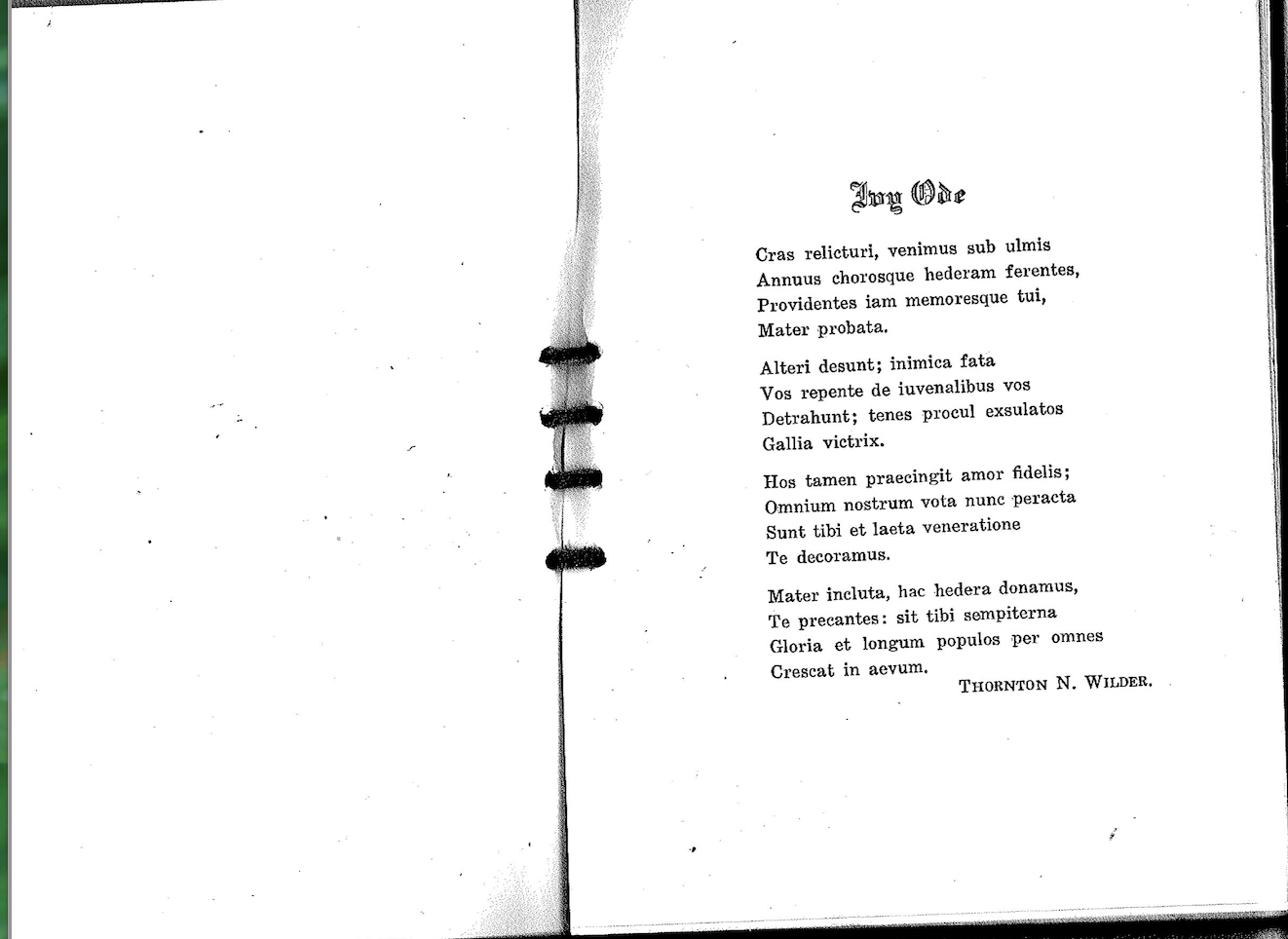

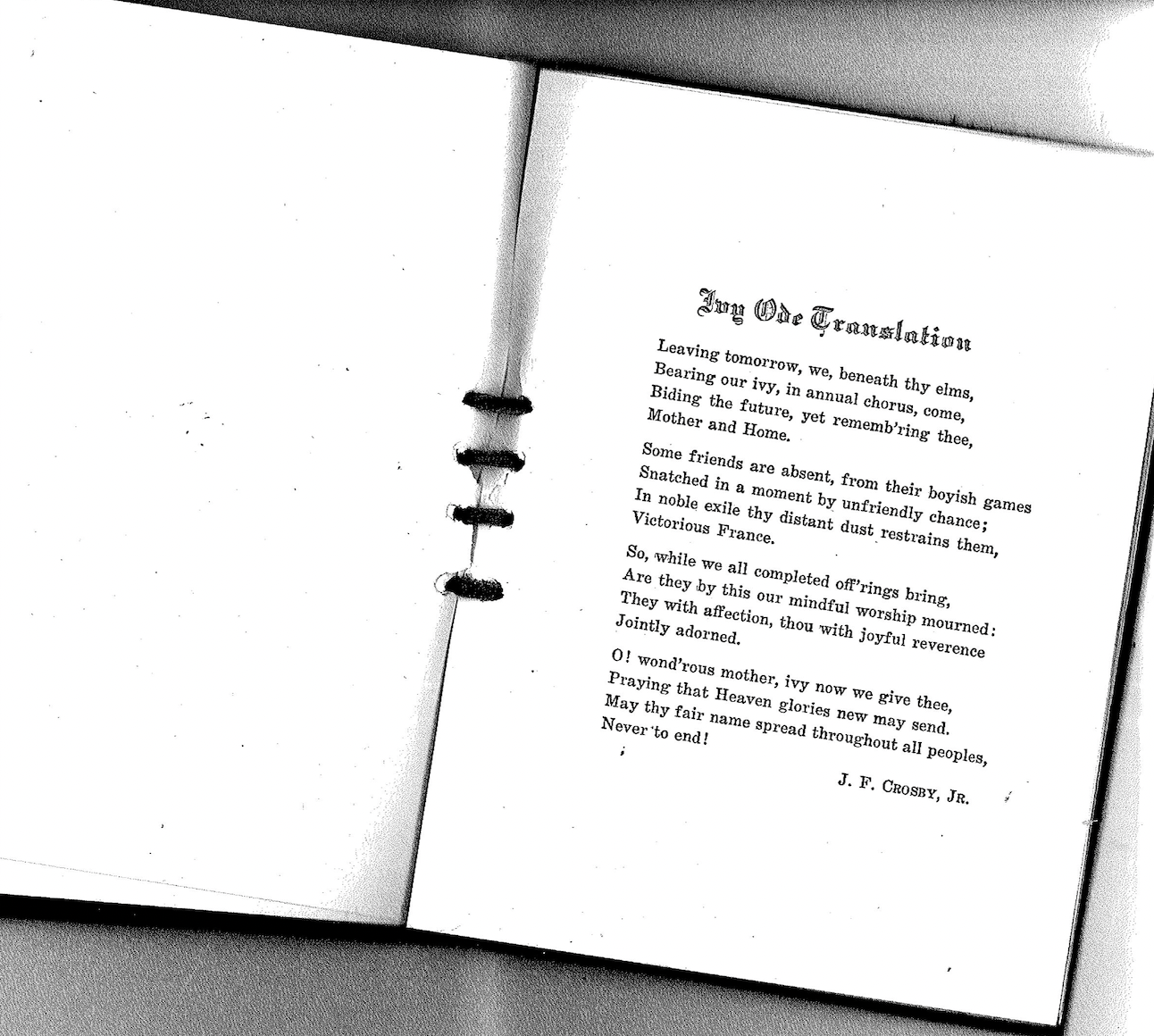

Not so my uncle. Thornton Wilder not only minored in Latin in college (voluntarily!), but a poem he wrote in Latin won a role at his commencement in 1920. He followed this honor by spending eight months at the American Academy in Rome. While taking part in an archeological dig under the streets of the Eternal City, he came face to face with the bygone Aurelius family. The encounter led him to grasp the commonality between their world and his. From his first novel, which he began writing the following summer, down to the end of his life, that commonality played a vital role in his work. References to the classics are tucked in everywhere in his novels and plays

But for sheer passion isn’t Thornton Wilder’s love for the classics clearest in The Ides of March? In Wilder’s take on Julius Caesar’s last days, written in white heat by a recently honorably discharged lieutenant colonel in Army Air Force intelligence, the severe and forbidding dictator who caused me so much trouble in the late ‘50s becomes a man of culture, a lover of poetry, even a sort of (serious) philosopher. Wanting his readers to feel the same vitality in stories and figures from the classical world that he did on his archaeological dig, Wilder employs the innovative approach of the epistolary novel. He thus banishes the past tense and narrative voice. And by using letters and other largely made-up texts (think graffiti, poetry, intercepts, journals, and commonplace books—the kitchen sink!), he helps the characters come vividly to life with all of their insecurities, ambitions, jealousies, hatreds, conspiracies, and reflections. Every time I read Ides, I feel that the long-dead Caesar, Cleopatra, Clodia, Catullus, and Cicero are so alive and well that I might pass them on the street. It’s little wonder that Wilder describes The Ides of March as a ”fantasy” rather than a novel.

While The Ides of March speaks to audiences in every era, there are times in the life of cultures and countries when the author’s exploration of the nature and destiny of humanity, of human freedom and governance, speaks more loudly than others. Isn’t this year one of them? In the aftermath of last week’s “super” primaries, and with a presidential election looming, it seems like the shape and fate of our own republic may be at stake. So on this particular Ides of March, certain passages in my uncle’s novel come easily to mind. Like the one that says “the crown of life is the exercise of choice”—a valuable reminder for citizens of a democracy. Or when Caesar points out that there is no liberty save in responsibility. In other words, we’re only truly free when we act for the good of our community.

However you feel about Thornton Wilder’s fantasy, I look forward to seeing you at the polls. As they say, and as I now heed with special attention: Beware the Ides of March.